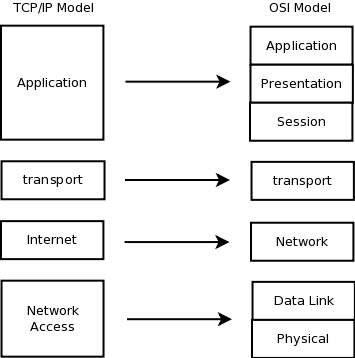

As mentioned earlier, the OSI reference model and the TCP/IP model are two open standard networking models that are very similar. However, the latter has found more acceptance today and the TCP/IP protocol suite is more commonly used. Just like the OSI reference model, the TCP/IP model takes a layered approach. In this section we will look at all the layers of the TCP/IP model and various protocols used in those layers.

The TCP/IP model is a condensed version of the OSI reference model consisting of the following 4 layers:

- Application Layer

- Transport Layer

- Internet Layer

- Network Access Layer

The functions of these four layers are comparable to the functions of the seven layers of the OSI model. Figure 1-9 shows the comparison between the layers of the two models.

The following sections discuss each of the four layers and protocols in those layers in detail.

Figure 1-9 Comparison between TCP/IP and OSI models

Application Layer

The Application Layer of the TCP/IP Model consists of various protocols that perform all the functions of the OSI model’s Application, Presentation and Session layers. This includes interaction with the application, data translation and encoding, dialogue control and communication coordination between systems.

The following are few of the most common Application Layer protocols used today:

Telnet – Telnet is a terminal emulation protocol used to access the resourses of a remote host. A host, called the Telnet server, runs a telnet server application (or daemon in Unix terms) that receives a connection from a remote host called the Telnet client. This connection is presented to the operating system of the telnet server as though it is a terminal connection connected directly (using keyboard and mouse). It is a text-based connection and usually provides access to the command line interface of the host. Remember that the application used by the client is usually named telnet also in most operating systems. You should not confuse the telnet application with the Telnet protocol.

HTTP – The Hypertext Transfer Protocol is foundation of the World Wide Web. It is used to transfer Webpages and such resources from the Web Server or HTTP server to the Web Client or the HTTP client. When you use a web browser such as Internet Explorer or Firefox, you are using a web client. It uses HTTP to transfer web pages that you request from the remote servers.

FTP – File Transfer Protocol is a protocol used for transferring files between two hosts. Just like telnet and HTTP, one host runs the FTP server application (or daemon) and is called the FTP server while the FTP client runs the FTP client application. A client connecting to the FTP server may be required to authenticate before being given access to the file structure. Once authenticated, the client can view directory listings, get and send files, and perform some other file related functions. Just like telnet, the FTP client application available in most operating systems is called ftp. So the protocol and the application should not be confused.

SMTP – Simple Mail Transfer Protocol is used to send e-mails. When you configure an email client to send e-mails you are using SMTP. The mail client acts as a SMTP client here. SMTP is also used between two mails servers to send and receive emails. However the end client does not receive emails using SMTP. The end clients use the POP3 protocol to do that.

TFTP – Trivial File Transfer Protocol is a stripped down version of FTP. Where FTP allows a user to see a directory listing and perform some directory related functions, TFTP only allows sending and receiving of files. It is a small and fast protocol, but it does not support authentication. Because of this inherent security risk, it is not widely used.

DNS – Every host in a network has a logical address called the IP address (discussed later in the chapter). These addresses are a bunch of numbers. When you go to a website such as www.cisco.com you are actually going to a host which has an IP address, but you do not have to remember the IP Address of every WebSite you visit. This is because Domain Name Service (DNS) helps map a name such as www.cisco.com to the IP address of the host where the site resides. This obviously makes it easier to find resources on a network. When you type in the address of a website in your browser, the system first sends out a DNS query to its DNS server to resolve the name to an IP address. Once the name is resolved, a HTTP session is established with the IP Address.

DHCP – As you know, every host requires a logical address such as an IP address to communicate in a network. The host gets this logical address either by manual configuration or by a protocol such as Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP). Using DHCP, a host can be provided with an IP address automatically. To understand the importance of DHCP, imagine having to manage 5000 hosts in a network and assigning them IP address manually! Apart from the IP address, a host needs other information such as the address of the DNS server it needs to contact to resolve names, gateways, subnet masks, etc. DHCP can be used to provide all these information along with the IP address.

Transport Layer

The protocols discussed above are few of the protocols available in the Application layer. There are many more protocols available. All of them take the user data and add a header and pass it down to the Transport layer to be sent across the network to the destination. The TCP/IP transport layer’s function is same as the OSI layer’s transport layer. It is concerned with end-to-end transportation of data and setups up a logical connection between the hosts.

Two protocols available in this layer are Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and User Datagram Protocol (UDP). TCP is a connection oriented and reliable protocol that uses windowing to control the flow and provides ordered delivery of the data in segments. On the other hand, UDP simply transfers the data without the bells and whistles. Though these two protocols are different in many ways, they perform the same function of transferring data and they use a concept called port numbers to do this. The following sections cover port numbers before looking into TCP and UDP in detail.

Port Numbers

A host in a network may send traffic to or receive from multiple hosts at the same time. The system would have no way to know which data belongs to which application. TCP and UDP solve this problem by using port numbers in their header. Common application layer protocols have been assigned port numbers in the range of 1 to 1024. These ports are known as well-known ports. Applications implementing these protocols listen on these port numbers. TCP and UDP on the receiving host know which application to send the data to based on the port numbers received in the headers.

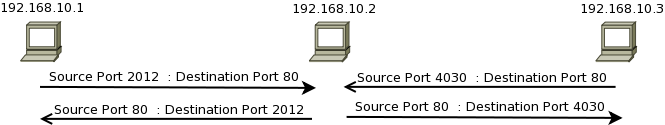

On the source host each TCP or UDP session is assigned a random port number above the range of 1024. So that returning traffic from the destination can be identified as belonging to the originating application. Combination of the IP address, Protocol (TCP or UDP) and the Port number forms a socket at both the receiving and sending hosts. Since each socket is unique, an application can send and receive data to and from multiple hosts. Figure 1-10 shows two hosts communicating using TCP. Notice that the hosts on the left and right are sending traffic to the host in the center and both of them are sending traffic destined to Port 80, but from different source ports. The host in the center is able to handle both the connections simultaneously because the combination of IP address, Port numbers and Protocols makes each connection different.

Figure 1-10 Multiple Sessions using Port Numbers

Table 1-1 shows the transport layer protocol and port numbers used by different common application layer protocols.

Table 1-1 Well-known Port Numbers

| Application Protocol | Transport Protocol | Port Number |

| HTTP | TCP | 80 |

| HTTPS | TCP | 443 |

| FTP (control) | TCP | 21 |

| FTP (data) | TCP | 20 |

| SSH | TCP | 22 |

| Telnet | TCP | 23 |

| DNS | TCP, UDP | 53 |

| SMTP | TCP | 25 |

| TFTP | UDP | 69 |

Transport Control Protocol (TCP)

TCP is one of the original protocols designed in the TCP/IP suite and hence the name of the model. When the application layer needs to send large amount of data, it sends the data down to the transport layer for TCP or UDP to transport it across the network. TCP first sets up a virtual-circuit between the source and the destination in a process called three-way handshake. Then it breaks down the data into chunks called segments, adds a header to each segment and sends them to the Internet layer.

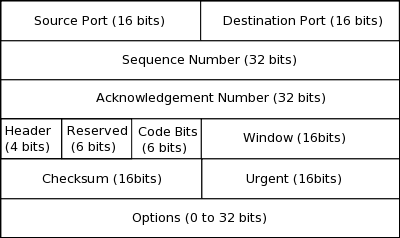

The TCP header is 20 to 24 bytes in size and the format is shown in Figure 1-11. It is not necessary to remember all fields or their size but most of the fields are discussed below.

Figure 1-11 TCP header

When the Application layer sends data to the transport layer, TCP sends the data across using the following sequence:

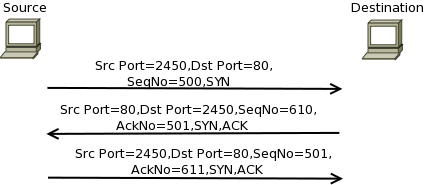

Connection Establishment – TCP uses a process called three-way handshake to establish a connection or virtual-circuit with the destination. The three-way handshake uses the SYN and ACK flags in the Code Bits section of the header. This process is necessary to initialize the sequence and acknowledgement number fields. These fields are important for TCP and will be discussed below.

Figure 1-12 TCP three-way handshake

As shown in Figure 1-12, the source starts the three-way handshake by sending a TCP header to the destination with the SYN flag set. The destination responds back with the SYN and ACK flag sent. Notice in the figure that destination uses the received sequence number plus 1 as the Acknowledgement number. This is because it is assumed that 1 byte of data was contained in the exchange. In the final step, the source responds back with only the ACK bit set. After this, the data flow can commence.

Data Segmentation – The size of data that can be sent across in a single Internet layer PDU is limited by the protocol used in that layer. This limit is called the maximum transmission unit (MTU). The application layer may send data much larger than this limit; hence TCP has to break down the data into smaller chucks called segments. Each segment is limited to the MTU in size. Sequence numbers are used to identify each byte of data. The sequence number in each header signifies the byte number of the first byte in that segment.

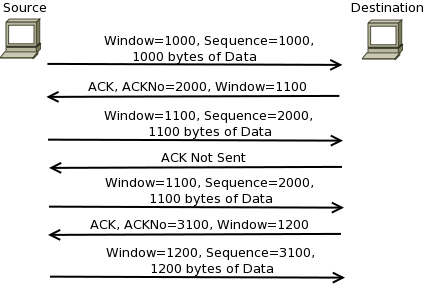

Flow Control – The source starts sending data in groups of segments. The Window bit in the header determines the number of segments that can be sent at a time. This is done to avoid overwhelming the destination. At the start of the session the window in small but it increases over time. The destination host can also decrease the window to slow down the flow. Hence the window is called the sliding window. When the source has sent the number of segments allowed by the window, it cannot send any further segments till an acknowledgement is received from the destination. Figure 1-13 shows how the window increases during the session. Notice the Destination host increasing the Window from 1000 to 1100 and then to 1200 when it sends an ACK back to the source.

Figure 1-13 TCP Sliding Window and Reliable delivery

Reliable Delivery with Error recovery – When the destination receives the last segment in the agreed window, it has to send an acknowledgement to the source. It sets the ACK flag in the header and the acknowledgement number is set as the sequence number of the next byte expected. If the destination does not receive a segment, it does not send an acknowledgement back. This tells the source that some segments have been lost and it will retransmit the segments. Figure 1-13 shows how windowing and acknowledgement is used by TCP. Notice that when source does not receive acknowledgement for the segment with sequence number 2000, it retransmits the data. Once it receives the acknowledgement, it sends the next sequence according to the window size.

Ordered Delivery – TCP transmits data in the order it is received from the application layer and uses sequence number to mark the order. The data may be received at the destination in the wrong order due to network conditions. Thus TCP at the destination orders the data according to the sequence number before sending it to the application layer at its end. This order delivery is part of the benefit of TCP and one of the purposes of the Sequence Number.

Connection Termination – After all data has been transferred, the source initiates a four-way handshake to close the session. To close the session, the FIN and ACK flags are used.

User Datagram Protocol (UDP)

The only thing common between TCP and UDP is that they use port numbers to transport traffic. Unlike TCP, UDP neither establishes a connection nor does it provide reliable delivery. UDP is connectionless and unreliable protocol that delivers data without overheads associated with TCP. The UDP header contains only four parameters (Source port, Destination Port, Length and Checksum) and is 8 bytes in size.

At this stage you might think that TCP is a better protocol than UDP since it is reliable. However you have to consider that networks now are far more stable than when these protocols where conceived. TCP has a higher overhead with a larger header and acknowledgements. The source also holds data till it receives acknowledgement. This creates a delay. Some applications, especially those that deal with voice and video, require fast transport and take care of the reliability themselves at the application layer. Hence in lot of cases UDP is a better choice than TCP.

Internet Layer

Once TCP and UDP have segmented the data and have added their headers, they send the segment down to the Network layer. The destination host may reside in a different network far from the host divided by multiple routers. It is the task of the Internet Layer to ensure that the segment is moved across the networks to the destination network.

The Internet layer of the TCP/IP model corresponds to the Network layer of the OSI reference model in function. It provides logical addressing, path determination and forwarding.

The Internet Protocol (IP) is the most common protocol that provides these services. Also working at this layer are routing protocols which help routers learn about different networks they can reach and the Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) that is used to send error messages across at this layer.

Almost half of the book is dedicated IP and Routing protocols so they will be discussed in detail in later chapters, but the following sections discuss these protocols in brief.

Internet Protocol (IP)

The Internet layer in the TCP/IP model is dominated by IP with other protocols supporting its purpose. Each host in a network and all interfaces of a router have a logical address called the IP address. All hosts in a network are grouped in a single IP address range similar to a street address with each host having a unique address from that range similar to a house or mailbox address. Each network has a different address range and routers that operate on layer 3 connect these different networks.

As IP receives segments from TCP or UDP, it adds a header with source IP address and destination IP address amongst other information. This PDU is called a packet. When a router receives a packet, it looks at the destination address in the header and forwards it towards the destination network. The packet may need to go through multiple routers before it reaches the destination network. Each router it has to go through is called a hop.

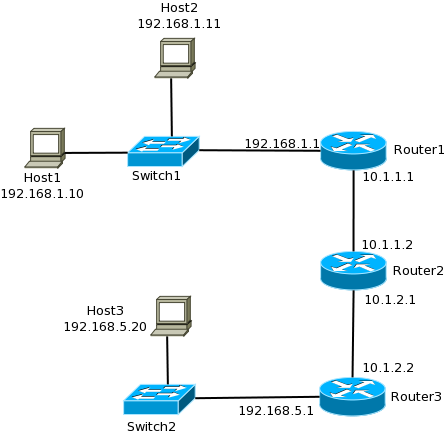

Figure 1-14 Packet flow in internetwork

Consider the Internetwork shown in Figure 1-14 to understand the routing process better. When Host1 needs to send data to Host2, it does not get routed because the hosts are in the same network range. The Data Link layer takes care of this. Now consider Host1 sending data to Host3. Host1 will recognize that it needs to reach a host in another network and will forward the packet to Router1. Router1 checks the destination address and knows that the destination network is toward Router2 and hence forwards it to Router2. Similarly Router 2 forwards the packet to Router3. Router3 is directly connected to the destination network. Here the data link layer takes care of the delivery to the destination host. As you can see, the IP address fields in the IP header play a very important role in this process. In fact IP addresses are so important in a network that the next Chapter is entirely dedicated to it!

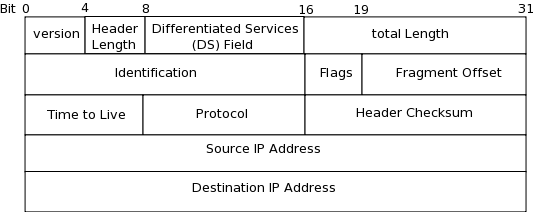

Figure 1-15 IPv4 Header

There are various versions of the Internet Protocol. Version 4 is the one used today and version 6 is slowly starting to replace it which is why it’s presence has increased on the CCNA Routing & Switching 200-120 exam compared to previous CCNA exam versions. Figure 1-15 shows the header structure of IPv4. The following fields make up the header:

Version – IP version number. For IPv4 this value is 4.

Header Length – This specifies the size of the header itself. The minimum size is 20 bytes. The figure does not show the rarely used options field that is of a variable length. Most IPv4 headers are 20 bytes in length.

DS Field – The differentiated Services field is used for marking packets. Different Quality-Of-Service (QoS) levels can be applied on different markings. For example, data belonging to voice and video protocols have no tolerance for delay. The DS field is used to mark packets carrying data belonging to these protocols so that they get priority treatment through the network. On the other hand, peer-to-peer traffic is considered a major problem and can be marked down to give in best effort treatment.

Total Length – This field specifies the size of the packet. This means the size of the header plus the size of the data.

Identification – When IP receives a segment from TCP or UDP; it may need to break the segment into chucks called fragments before sending it out to the network. Identification fields serves to identify the fragments that make up the original segment. Each fragment of a segment will have the same identification number.

Flags – Used for fragmentation process.

Fragment Offset – This field identifies the fragment number and is used by hosts to reassemble the fragments in the correct order.

Time to Live – The Time to Live (TTL) value is set at the originating host. Each router that the packet passes through reduces the TTL by one. If the TTL reaches 0 before reaching the destination, the packet is dropped. This is done to prevent the packet from moving around the network endlessly.

Protocol – This field identifies the protocol to which the data it is carrying belongs. For example a value of 6 implies that the data contains a TCP segment while a value of 17 signifies a UDP segment. Apart from TCP and UDP there are many protocols whose data can be carried in an IP packet.

Header Checksum – This field is used to check for errors in the header. At each router and at the destination, a cyclic redundancy check performed on the header and the result should match the value stored in this field. If the value does not match, the packet is discarded.

Source IP address – This field stores the IP address of the source of the packet.

Destination IP address – This field stores the IP address of the destination of the packet.

Figure 1-16 Source and Destination IP address

Figure 1-16 shows how Source and Destination IP address is used in an IP packet. Notice how the source and destination addresses changed during the exchange between HostA and HostB

Routing Protocols

In Figure 1-14, Router1 knew that it needed to send the packet destined to Host3 toward Router2. Router2 in turn knew that the packet needed to go toward Router3. To make these decisions, the routers need to build their routing table. This is a table of all networks known by it and all the routers in the internetwork. The table also lists the next router towards the destination network. To build this table dynamically, routers use routing protocols. There are many routing protocols and their sole purpose is to ensure that routers know about all the networks and the best path to any network. Chapter 4 and Chapter 5 discuss the routing process and some routing protocols in detail.

Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP)

ICMP is essentially a management protocol and messaging service for IP. Whenever IP encounters an error, it sends ICMP data as an IP packet. Some of the reasons why an ICMP message can be generated are:

Destination Network Unreachable – If a packet cannot be routed to the network in which the destination address resides, the router will drop the packet and generate an ICMP message back to the source informing that the destination network is unreachable.

Time Exceeded – If the TTL of a packet expiries (reduces to zero), the router will drop it and generate an ICMP message back to the source informing it that the time exceeded and the packet could not be delivered.

Echo Reply – ICMP can be used to check network connectivity. Popular utility called Ping is used to send Echo Requests to a destination. In reply to the request, the destination will send back an Echo reply back to the source. Successful receipt of Echo reply shows that the destination host is available and reachable from the source.

Network Access Layer

The Network Access layer of the TCP/IP model corresponds with the Data Link and Physical layers of the OSI reference model. It defines the protocols and hardware required to connect a host to a physical network and to deliver data across it. Packets from the Internet layer are sent down the Network Access layer for delivery within the physical network. The destination can be another host in the network, itself, or a router for further forwarding. So the Internet layer has a view of the entire Internetwork whereas the Network Access layer is limited to the physical layer boundary that is often defined by a layer 3 device such as a router.

The Network Access layer consists of a large number of protocols. When the physical network is a LAN, Ethernet at its many variations are the most common protocols used. On the other hand when the physical network is a WAN, protocols such as the Point-to-Point Protocol (PPP) and Frame Relay are common. In this section we take a deep look at Ethernet and its variations. WAN protocols are covered in detail in Chapter 11.

Before we explore Ethernet remember that:

Network Access layer uses a physical address to identify hosts and to deliver data.

- The Network Access layer PDU is called a frame. It contains the IP packet as well as a protocol header and trailer from this layer.

- The Network Access layer header and trailer are only relevant in the physical network. When a router receives a frame, it strips of the header and trailer and adds a new header and trailer before sending it out the next physical network towards the destination.